At a tipping point? Workplace mental health and wellbeing March 2017 Contents

Foreword 01

Introductory letter 02

Executive Summary 03

The importance of mental health and wellbeing in the workforce 04

The trends driving interest in workplace mental health and wellbeing 10

Challenges in improving workplace mental health and wellbeing 14

Collective actions for stakeholders 20

Endnotes 28

Contacts 32

The Deloitte Centre for Health Solutions The Deloitte UK Centre for Health Solutions is the research arm of Deloitte LLP’s healthcare and life sciences practices. Our goal is to identify emerging trends, challenges, opportunities and examples of good practice, based on primary and secondary research and rigorous analysis. The Centre’s team of researchers seeks to be a trusted source of relevant, timely, and reliable insights that encourage collaboration across the health value chain, connecting the public and private sectors, health providers and purchasers, patients and suppliers. Our aim is to bring you unique perspectives to support you in the role you play in driving better health outcomes, sustaining a strong health economy and enhancing the reputation of our industry. In this publication, references to Deloitte are references to Deloitte LLP, the UK member firm of DTTL. Welcome to Deloitte’s report: At a tipping point? Workplace mental health and wellbeing. Public awareness of the importance of good workplace mental health and wellbeing is growing, as is the moral, societal and business case for improving it. Yet, despite this, many employers experience numerous challenges in improving their performance in supporting employee mental health and wellbeing. Our report is designed as a call to action for employers, whatever their current position, as well as a practical guide on how to address some of the main barriers to improvement. A number of recent developments are helping to raise the profile of these important issues, including the publication of Business in the Community’s National Employee Mental Wellbeing Survey and Mental Health toolkit for employers in late 2016; the Prime Minister’s January 2017 announcement of an independent report on companies’ actions to support mental health; and Mind’s first Workplace Wellbeing Index. The impetus for this report was The insight we gained in working with one of our charity partners, the mental health charity Mind, and its Workplace Wellbeing team. Further insights were provided by working on a number of key projects on both mental and physical health in the workplace; including projects with occupational and corporate health providers over the past five years. This experience has given us a broad and differentiated perspective on the importance of workplace mental health and wellbeing. Interviews with employers undertaken over a number of years suggest that employer and employee attitudes to mental health are changing. We believe we are on the cusp of a change similar to that seen with the corporate responsibility movement in the mid-1990s when momentum gathered pace, such that by the early 2000s corporate responsibility reporting had become mainstream. This report presents our views on:

• the importance of mental health in the workplace

• the changing environment for workplace wellbeing

• the challenges in implementation and in changing employer and employee attitudes

• solutions to current and future challenges. We hope that you find the research insights informative, thought-provoking and of practical help for employers seeking to play a greater role in supporting the mental health and wellbeing of their employees. As always we welcome your feedback and comments. Karen Taylor Elizabeth Hampson Director, Centre for Health Solutions Senior Manager, Monitor Deloitte Foreword 01 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Emma Mamo, Head of Workplace Wellbeing, Mind Over the past few years, employee wellbeing has been rising up the agenda for employers in the UK. A key aspect of this is the mental health of staff. Organisations depend on having a healthy and productive workforce: we know that when employees feel their work is meaningful and they are valued and supported, they tend to have higher wellbeing levels, be more committed to the organisation’s goals and perform better. We appreciate the work that Deloitte has done to support Mind and other organisations to promote this agenda including producing this report. I joined Mind in 2007 and have led our campaigning for mentally healthy workplaces since 2010. Over the course of our work we have seen an evolution in how employers view workplace wellbeing, with the focus shifting from the reactive management of sickness absence to a more proactive effort around employee engagement and preventative initiatives. This shift has given employers the impetus to look at the mental health of their staff from a different perspective; with an increasing acknowledgement that they need to do more to support the mental health of their staff. Despite these strides there’s still a long way to go. Mental health problems can affect anyone in any industry and yet mental health is often still a taboo subject. Our poll in 2014 revealed that a staggering 95 per cent of people who have had to take time off due to workplace stress did not feel able to give their employer the real reason, and as the Time to Change Public Attitudes survey indicated in 2014, 49 per cent of people still feel uncomfortable talking to an employer about their mental health. There is clearly still work to do when it comes to breaking down stigma and providing the type of open and supportive culture that enables staff to be honest with their manager, to access support and to enjoy a healthy working life. In seeking to move from rhetoric to reality employers must mainstream good mental health and make it a core business priority. A mentally healthy workplace and increased employee engagement are interdependent – by looking after employee’s mental wellbeing, staff morale and loyalty, innovation, productivity and profits will rise. In order to create a mentally healthy workplace, we recommend that employers put in place a comprehensive strategy to help people stay well at work, to tackle the root causes of work-related mental health problems and to support people who are experiencing a mental health problem. Many of the measures we recommend are small and inexpensive. Regular catch‑ups with managers, flexible working hours, promoting work/life balance and encouraging peer support; can make a huge difference to all employees, whether or not they have a mental health problem. But above all, creating a culture where staff feel able to talk openly about mental health at work is the most important part. At Mind, over the next five years, we want to support a million people to stay well and have good mental health at work. To help achieve this, we have launched a Workplace Wellbeing Index which will enable employers to celebrate the good work they’re doing to promote staff mental wellbeing and get the support they need to be able to do this even better. The Index is a benchmark of best policy and practice and will publicly rank employers on how effectively they are addressing staff mental wellbeing. Be part of the movement for change in workplace wellbeing by starting your journey towards better mental health in your organisation today. Introductory letter 02 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Executive Summary Mental health and wellbeing describes our mental state – how we are feeling and how well we can cope with day-to-day life. Promoting mental health and wellbeing in the workplace is important for employees, their employers, society and the economy. This is because poor mental health impacts individuals’ overall health, their ability to work productively (if at all), their relationships with others, and societal costs related to unemployment, poor workplace productivity and health and social care. Employers have a key role to play in supporting employees’ mental health and wellbeing. The government has given increasing recognition to the importance of workplace mental health as have forward-looking employers who are creating strategies around workplace mental wellbeing. This change in emphasis has been supported by a number of trends, namely greater public awareness of mental health, increasing political interest in mental health and greater transparency around corporate responsibility. In particular, over the past 25 years, policies relating to mental health have referenced the role of employers more explicitly and with increasing frequency.

Our report identifies a number of actions for employers, employees and key stakeholders across society:

• For employers, it is important to raise the priority given to mental health and wellbeing in order to move toward a culture which proactively manages mental wellbeing. This could be through the appointment of health and wellbeing leads, or signing-up for corporate pledges. It is also important to take stock and monitor performance using validated tools to track quantifiable measures and gain momentum and buy-in around wellbeing programmes. This can allow organisations to implement relevant initiatives, such as mental health training for managers, and track and promote their success in line with other business metrics.

• For employees, it is important to become actively engaged in their own health and wellbeing and participate in strategies that promote both mental and physical wellbeing. This includes employee involvement in workplace programmes around mental health, with potential actions including volunteering as a mental health champion or making efforts to address stigma through sharing personal stories. Employees should also be made aware of the support available to colleagues and any strategies available to support employee mental wellbeing.

• More broadly, society and the state should encourage collaboration with corporate employers to improve workplace mental health by investing in research and developing an improved evidence base, forming strategic partnerships with other stakeholder to spread best practice, and supporting workplace wellbeing initiatives such as the ‘Time to Change’ employer pledge and ‘This is Me’. Policymakers also need to focus on policies that provide aligned incentives to encourage companies to take charge of employees’ mental health and promote actions that improve mental wellbeing. Currently, there are a number of promising developments in the workplace mental wellbeing space which should enable employers to better support employees, as well as to prioritise, quantify and track employee mental health and wellbeing. Whilst the speed at which workplace mental wellbeing strategies are successfully implemented may vary, we believe that we are reaching a tipping point in the priority now being given to addressing mental health issues in the workplace and the roles and responsibilities of employers, a positive move which has benefits for employees, employers and society. Despite these positive trends, we see a number of challenges for employers in successfully implementing workplace mental health and wellbeing programmes. These include a failure to see employee mental health as a priority against other operational demands; a reactive approach to implementing mental wellbeing policies rather than focussing on prevention; a lack of understanding around how the company currently performs in this space; a poor evidence base to measure the return on investment of any programmes; and a lack of best practice examples to promote improvements. Workplace stigma and perceptions around mental health underlie and exacerbate many of these challenges. 03 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing In any one year, over one in four people in the general population and one in six workers is likely to be suffering from a mental health condition. With over 31 million people in work in the UK, this is equivalent to over five million workers who could be suffering from a mental health condition each year.5, 6 The UK has made significant progress in opening up conversations around mental health and wellbeing and in attempting to reduce the stigma it invokes. However, this progress appears to be occurring at a slower rate in the workplace, compared to conversations occurring in public spaces more generally. Reporting mental health issues in the workplace is much lower than for other ill health conditions due to reasons of stigma and a lack of knowledge and training on how to support friends and colleagues in the workplace. Yet, workplace mental health and wellbeing is a significant issue which employers have a moral as well as economic reason to address. Employees who can take proactive measures to manage their mental health and wellbeing, can give their best at work. Poor mental health impacts employees, their families, employers and the state. An acknowledgement of this economic impact is reflected in the increased focus on mental health in policymaking, especially the political commitments to achieve parity in treatment of mental and physical health, and the increasing role of employers to support their employees’ mental health. While there are close links between mental and physical health and wellbeing, this report focuses on mental health and wellbeing in the workplace, and the need for dedicated strategies to be integrated in overarching human resources (HR) and health and safety policies. References to wellbeing in the report are therefore to mental wellbeing (see sidebar for further definitions). Definitions of mental health and wellbeing Wellbeing is defined by the UK Department of Health as feeling good and functioning well, and comprises each individual’s experience of their life and a comparison of life circumstances with social norms and values. Wellbeing can be both subjective and objective.

1 Mental wellbeing, as defined by Mind, describes your mental state. Mental wellbeing is dynamic. An individual can be of relatively good mental wellbeing, despite the presence of a mental illness. If you have good mental wellbeing you are able to:

• feel relatively confident in yourself and have positive self-esteem

• feel and express a range of emotions

• build and maintain good relationships with others

• feel engaged with the world around you

• live and work productively

• cope with the stresses of daily life, including work-related stress

• adapt and manage in times of change and uncertainty.

2 Mental health is defined by the WHO, as a state of mental and psychological wellbeing in which every individual realises his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community. Mental health is determined by a range of socioeconomic, biological and environmental factors.

3 Work-related stress, as defined by the WHO, is the response people may have when presented with demands and pressures that are not matched to their abilities leading to an inability to cope, especially when employees feel they have little support from supervisors as well as little control over work processes.

4 The importance of mental health and wellbeing in the workforce

At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing: Impact of mental ill health to employees, employers and society The importance of mental health and wellbeing

• In 2015-16 there were 488,000 reported cases of work-related stress, anxiety or depression

• 77 per cent of employees have experienced symptoms of poor mental health in their lives

• Mental ill health has negative impact on physical health Impact on employees

• The total cost of mental ill health to UK employers was estimated at £26 billion, costing £1,035 per employee, per year in 2007

• Only 2 in 5 employees are working at peak performance

• Studies suggest that presenteeism from mental ill health alone costs the UK economy £15.1 billion per annum, in what is almost twice the business cost as actual absence from work Impact on employers

• Mental health (not specific to workplace wellbeing) costs the UK £70 billion each year, equivalent to 4.5 per cent of GDPv

• Mental health is a growing cause of incapacity benefits

• Evidence shows that poor mental health increases the costs of physical ill health Impact on society The average person spends 90,000 hours of their life working. Poor employee mental health can be due to factors internal or external to the workplace and, without effective management, can seriously impact employees’ productivity, career prospects and wider health. While there is increasing awareness of the impacts of poor employee mental health, there remains a disconnect between employers’ intentions and perceptions and what is actually happening in the workplace. This means that employees often do not get the help they need to maintain a fulfilling and productive working life, and some line managers are frustrated by the lack of support to do what they know is right. The strategies and statistics in this report are relevant to employees who require support for pre-existing mental health conditions, those who develop conditions due to factors external to work, and those who experience poor mental health as a direct consequence of their roles and workplace environment. In 2015-16, work-related stress accounted for 37 per cent of all work-related ill health cases and 45 per cent of all working days lost due to ill health.

7 The total number of working days lost due to work-related stress, anxiety and depression was 9.9 million days, an average of 24 days lost per case.

8 However, according to data from Mind, 95 per cent of employees who have taken off time due to stress named another reason, such as an upset stomach or headache.

9 The Mental Health at Work Report 2016, based on the Business in the Community’s National Employee Mental Wellbeing survey, provides an up-to-date and comprehensive assessment of workplace mental health in the UK. Participants took part via a YouGov panel survey (3,036 respondents) and a public open survey (16,246 respondents). Figure 2 highlights the main findings from the survey.

10, 11 Sources:

- Health and Safety Executive, Work related stress, anxiety and depression statistics in Great Britain 2016, HSE, 2016;

- (ii) Mental health at Work Report 2016, Business in the Community, 2016; (iii) Bringing together physical and mental health, a new frontier for integrated care, The King’s Fund, 2016; (iv), Mental health at work: developing the business case, Centre for Mental Health, 2007; (v) Mental health and work, OECD, 2014; (vi) Mental illness ‘top reason to claim incapacity benefit‘, BBC news, 2011 Impact on employees 05 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing: Findings from the National Employee Mental Wellbeing survey Source: Mental health at Work Report 2016, Business in the Community, 2016 84% of employees have experienced physical, psychological, or behavioural symptoms of poor mental health where work was a contributing factor Whilst 60% of board members and senior managers believe their organisation supports people with mental health issues, only 11% discussed a mental health problem with their line manager In the case of a staff member with depression: 68% of female managers would feel confident responding to the issue, compared to 58% of male managers 9% of employees who experienced symptoms of poor mental health experienced disciplinary action, up to and including dismissal 76% of line managers believe employee wellbeing is their responsibility 49% would find even basic training in common mental health conditions useful 22% have received some form of training on mental health at work 76% 22% 49% 35% of employees did not approach anyone for support on the most recent occasion they experienced poor mental health 86% would think twice before offering to help a colleague whose mental health they were concerned about 68% 58% 06 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Low levels of employee wellbeing negatively impact productivity, but more importantly have a significant negative impact on employees’ overall health.

A 2015 report based on a meta-analysis of 228 research studies on the topic found a link between causes of workplace stress and health outcomes:

• job insecurity increases the odds of reporting poor health by about 50 per cent

• high job demands raise the odds of having a physician-diagnosed illness by 35 per cent • long work hours increase mortality by almost 20 per cent.

12 Stigma is another challenge facing employees suffering from ill mental health, especially if there is little understanding of mental health in the workplace. Whilst general public awareness and acceptance of mental health has increased, the workplace has been slow to follow suit. For example, 48 per cent of people with mental health problems said they would not be comfortable talking to their employer and only 55 per cent of employees believe their manager is concerned about their wellbeing.

13, 14 Finally, the personal cost of mental illness is extensive, from loss of income and debt, (one in four adults with mental health problems are in debt), to wider family challenges.

15 A study by the Centre for Social Justice acknowledges that family breakdown is both a cause and effect of poor mental health.

16 Family relationship challenges may become further exacerbated where loss of income occurs as a result of poor mental health of a primary breadwinner. While the underlying causes of mental illness are complex and multifaceted, pre-existing mental health conditions, new conditions related to changes in an individual’s personal situation and the consequences of work-related deterioration of mental wellbeing among staff create significant costs for employers. The financial cost of poor mental health to employers is most easily illustrated through the sickness absence of employees, as discussed above.

17 However, absence is not the only cost associated with poor mental health. Other costs include:

• presenteeism, which is the loss in productivity that occurs when employees come to work but function at less than full capacity because of ill health

• turnover costs, which is the cost of replacing staff who leave their job due to a mental health problem. Given this complexity, total business costs of mental ill health are difficult to define. To date, figures from a 2007 Centre for Mental Health report are those most consistently cited by organisations such as Mind, the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (Acas), Business in the Community and the UK Government. The report calculated that mental ill health at work costs UK businesses £26 billion. Later analysis raised this to £30 billion.

19 The split was estimated at around 10 per cent due to the cost of replacing staff, 30 per cent cost due to sickness absence, and 60 per cent cost due to reduced productivity at work. The report further suggests that improving the management of mental health in the workplace, including prevention and early identification of problems could enable employers to save 30 per cent or more of these costs.

20 Nevertheless, while improving support for employees with a pre-existing condition or those suffering a period of mental ill health is crucial, recognising that we all have varying states of mental wellbeing at all times is equally important. There is an additional cost to employers that results from staff not being engaged and enthusiastic, which extends wider than presenteeism. Acknowledging this allows for effective preventative actions that both the individuals and the business can implement to keep more employees in the top quartile of wellbeing for longer. However, the lack of precision around measuring the cost of mental health to employers also impacts on the ability to measure savings and benefits accruing from workplace wellbeing programmes. The lack of clear return of investment (ROI) benefits for prevention programmes has been a key challenge to wider adoption of good practice interventions and initiatives. This is a topic we will explore later in this report. Impact on employers 07 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Poor mental wellbeing is also costly to society. This includes the costs to the public sector and strains on the National Health Service (NHS). Costs to the public sector include disability benefits, as those suffering from mental health problems are also more likely to be unable to work. In 2015, 48 per cent of Employment and Support Allowance recipients had a mental or behavioural disorder as their primary condition.

21 Overall costs of poor mental wellbeing to the NHS include a disproportionate use of NHS services as a complication from under-managed mental health, and deterioration of individuals’ physical health linked with poor mental wellbeing. Evidence from a 2016 King’s Fund study indicates that:

• poor physical health contributes greatly to a reduced life expectancy of 15 to 20 years of people with severe mental illnesses against the general population

• depression and anxiety disorders lead to significantly poorer outcomes among people with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other longterm conditions (LTCs)

• 12 to 18 per cent of all NHS expenditure on LTCs is linked to poor mental health and wellbeing – between £8 billion and £13 billion in England each year

• people with mental health problems use significantly more unplanned hospital care for physical health needs than the general population, showing a 3.6-fold higher rate of potentially avoidable emergency admissions.

22 In 2014, NHS England published the Five Year Forward View to set out a new shared vision for the future of the NHS based around new models of care.

23 Two years later, in 2016, a separate document entitled the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health was published by the Mental Health Taskforce, with the aim of improving mental health outcomes across the health and care system. Part of the analysis within this report shows the significant link between physical and mental healthcare costs and the corresponding impact on state health and social care spending. For example, physical healthcare costs for people with type 2 diabetes with poor mental health are 50 per cent higher than for those diabetes patients in good mental health, resulting from increased rates of avoidable hospital admissions and complications in this group. In total, the presence of poor mental health is estimated to be responsible for £1.8 billion of spend on the type 2 diabetes pathway.

24 In 2014, the OECD conducted a report on mental health and work in the UK, estimating a total cost of £70 billion.

25 The economic and social cost breakdown of these overall costs is likely to be in line with a similar study carried out in 2009-10 by the Centre for Mental Health:

• 50 per cent human costs, based on a valuation of the negative impact of mental health on sufferers’ quality of life

• 30 per cent cost of output losses due to reduced ability to work

• 20 per cent direct health and social care costs.

26 Impact on society 08 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing The above analysis indicates clearly that poor mental health and wellbeing at work is a significant and urgent challenge. It is important not only to individuals and their families, but there are also significant incentives for all employers and the state to act. In subsequent chapters we explore:

• the trends driving an interest in workplace mental health and wellbeing (Part 2)

• the challenges of implementing workplace mental health and wellbeing initiatives (Part 3)

• collective actions for stakeholders to address the identified challenges (Part 4). Figure 3: Costs of mental ill health to the NHS Source: (i) A call to action: achieving parity of esteem; transformative ideas for commissioners, NHS England, 2014; (ii) The Five Year Forw The trends driving interest in workplace mental health and wellbeing: Trends supporting greater public awareness of mental health Public interest in workplace wellbeing in general, and mental wellbeing in particular, has grown significantly in recent years. This part of the report explores the reasons for this increased interest including:

• greater public awareness of mental health

• increasing political attention and associated policy changes

• workplace trends and increased emphasis on employer responsibilities. Greater public awareness of mental health Levels of interest and awareness around mental health have increased over the last ten years, driven by high-profile public media campaigns such as Time to Change, the emergence of new employer-driven networks and alliances to support those suffering from poor mental health, and high-profile media stories about personal experiences with mental health

27 Source: National Attitudes to Mental Illness 2014-2015, Time to Change, 2015 2.5 million people have improved attitudes toward mental health between 2011 and 2015 7% rise in willingness to continue a relationship with a friend with a mental health problem between 2009 and 2015 91% agreed that we need to adopt a more tolerant attitude to people with mental health problems 7% rise in willingness to work with someone with a mental health problem between 2009 and 2015 10 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Increasing political attention and associated policy changes Over the past 25 years the Government and policy makers have increased the priority given to improving awareness and treatment of mental health. More specifically, there was a subtle shift in the direction of government policies towards community engagement, in the 2009 ‘New Horizons-Towards a shared vision for mental health action programme’.

28 This was followed by the 2011 cross-government mental health outcomes strategy ‘No Health Without Mental Health’. Key elements of this strategy included improving mental health outcomes by:

• ensuring that mental health is high on the government’s agenda

• promoting mental health initiatives and providing targeted funding

• taking a life course approach and prioritising early intervention

• tackling health inequalities by supporting diversity and increasing patient empowerment • challenging stigma by working with programmes that improve public awareness and attitudes

• improving access to mental health services for those in the criminal justice system.

29 Indeed, the increasing prominence of mental health policy is illustrated by the reduction in the time between subsequent policies addressing an element of mental health treatment or prevention and shifts towards a parity of esteem between mental and physical health, which the government has pledged to achieve by 2020 . In 2013 the UK’s first Shadow Minister for Mental Health was established by the Labour Party and in early 2016 David Cameron addressed mental health in a public speech, announcing almost £1 billion of investment and pledging a revolution in addressing mental health.

30 In her January 2017 speech on mental health, PM Theresa May expressed the wish “to employ the power of government as a force for good to transform the way we deal with mental health problems right across society”. The PM unveiled a package of reforms to improve mental health support at every stage of a person’s life, including an announcement of an independent report on companies’ work to support mental health and the encouragement for thirdsector organisations to partner further with leading employers and mental health groups.

31 11 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Figure 5: Developments in mental health policy Source: Department of Health, 2017; NHS England, 2017; UK Government, 2017 Quality requirements for major medical conditions. Mental health section refers to the importance of workplace supporting mental health Recognised link between employment and mental health in the workplace Increasing interest in early intervention for mental health problems Dedicated mental health strategy Creation of a new legal responsibility for the NHS to achieve parity between physical and mental health Nationwide five year strategy across healthcare Dedicated mental health strategy, referencing employers Announcement of independent report on companies’ work to support mental health Added emphasis on mental health 1983 Mental Health Act 1992 Health of the Nation White Paper 1999 National Service Framework 2004 National Service Framework: five years on 2005 Mental Capacity Act 2005 Health, Work and Wellbeing 2007 Mental Health Act Amendment 2007 Department of Health boosts mental health spend 2010 New Horizons – Towards a shared vision for mental health 2011 Sickness Absence Review 2011 Improving Access to Psychological Therapies 2011 No Health without Mental Health 2012 Health and Social Care Act 2013 First Shadow Minister for Mental Health 2014 Health and Work Service 2014 NHS Five Year Forward View 2015 Fit for Work Launch 2016 NHS Five Year Forward View for Mental Health 2017 PM Theresa May speech 2009 Occupational Health Advice Service started Start of a decade-long initiative on wellbeing in the workplace Defines the rights of people with mental health problems regarding assessment and treatment in hospital, and community including the law to be detained for treatment 12 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Mental health has been similarly prioritised in the devolved administrations across the UK. The Scottish government has set a vision that by 2025 people in Scotland should have a world-leading working life where fair work drives success, wellbeing and prosperity for individuals, businesses, organisations and for society as part of its Fair Work Convention.

32 Northern Ireland’s Assembly recently had a crossparty vote supporting a mental health champion programme.

33 Finally the Welsh government set up a 10 year strategy for mental health and wellbeing, published in 2012, and the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act (2015) describes a commitment to fostering the wellbeing of the nation.

34 However, this increase in political rhetoric and the growing burden of mental ill health on public services has thus far not been matched by adequate shifts in funding. According to the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health, mental health accounts for 23 per cent of all NHS activity, while NHS spending on secondary mental health services is equivalent to around half (12 per cent).

35 BBC analysis (covering two thirds of all English mental health trusts) revealed an overall reduction in real-term spending of 2.3 per cent since 2011-12, with ten trusts projecting further cuts next year.

36 At the same time, referrals to mental health teams had increased by 16 per cent on average. A survey of Finance Directors and Chief Financial Officers at more than half of all English mental health trusts revealed that only 50 per cent of providers reported that they had received a real-terms increase in funding of their services in 2015-16.

37 There remains therefore some uncertainty around how easily rhetoric on mental health and parity of esteem with physical health can translate into reality. Faced with these pressures, government policy has increasingly called out the responsibility of employers to safeguard the mental health and wellbeing of their employees. For example, the 2011 Sickness Absence Review recommended that expenditure by employers targeted at keeping sick employees in work or speeding their return to work should attract tax relief.

38 In addition, the Five Year Forward View states that “there would be merit in extending incentives for employers in England who provide effective National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended workplace health programmes for employees”.

39 NICE recommends employers to:

• make health and wellbeing a core priority for the top management of the organisation • value the strategic importance and benefits of a healthy workplace

• encourage a consistent, positive and preventative approach to employee health and wellbeing

• include employee participation in planning and implementation of wellbeing strategies. However, these guidelines are not mandatory and may not sufficiently incentivise organisations’ adoption of these recommendation.

40, 41 Workplace trends and increased emphasis on employer responsibilities Regulations around workplace health have become increasingly sophisticated, moving from general health and safety legislation and working with disabilities to specifying employee health, wellbeing and mental health. For example, since the 1974 Health and Safety at Work Act, employers have a legal responsibility to ensure the health, safety and welfare of their employees at work which includes minimising the risk of stress-related illness or injury.

42 An additional dynamic is the growing necessity and desire of companies to remain attractive to millennials. By 2025, millennials (born in 1983 or later) will make up 75 per cent of the workforce. According to the Deloitte Millennial Survey, up to 70 per cent of this cohort would consider working independently through digital means in the future, meaning forward-looking companies are anticipating their needs and trying to boost their attractiveness to recruit millennials. Making a company attractive to millennials includes, but is not limited to, focusing on the purpose and positive impact of a business both internally and externally. The survey shows a perception gap between millennials expectations and their perceptions of business: 37 per cent of millennials would place workplace wellbeing as a key priority for senior leadership, however only 17 per cent perceive this to be currently the case.

43 13 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing As discussed in the previous sections of this report there is a moral, legal and economic case for giving greater attention to employees’ mental health and wellbeing. However, evidence on workplace wellbeing suggests that employers are not as of yet responding effectively to the task. Recent evidence on the state of implementation of workplace mental wellbeing strategies shows that:

• 72 per cent of workplaces have no mental health policy

44 • 56 per cent of people would not employ an individual who had a history of depression, even if they were the most suitable candidate

45 • 27 per cent of employees consider their organisations take a much more reactive than proactive approach to wellbeing

46 • 92 per cent of people with mental health conditions believe that admitting to these in the workplace would damage their career.

47 This part of the report explores why such negative views relating to mental health in the workplace occur, and how this impacts the implementation of workplace mental wellbeing schemes. Specifically it explores five inter-related themes that challenge successful implementation of workplace mental wellbeing programmes, including how the stigma around mental health underlies and worsens many of the stated challenges . Challenges in improving workplace mental health and wellbeing: Key implementation challenge themes for employers Failure to see mental health and wellbeing as a priority Mental health and wellbeing policies are reactive and driven by staff events or experience, not proactive and preventative Lack of insight around current performance (including recruitment, retention and presenteeism) Poor evidence base to measure return on investment of wellbeing strategies Lack of collective knowledge of best practice 1 2 3 4 5 Source: Deloitte research, analysis and interviews 14 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Challenge theme 1: Failure to see mental health and wellbeing as a priority There are several reasons why a business will not prioritise acting on mental health and wellbeing. The first is that there may be high operational demands, with insufficient energy, time and resources available to acknowledge and address workforce mental health and wellbeing. Currently 52 per cent of organisations believe employee wellbeing is only a focus in their business when things are going well.

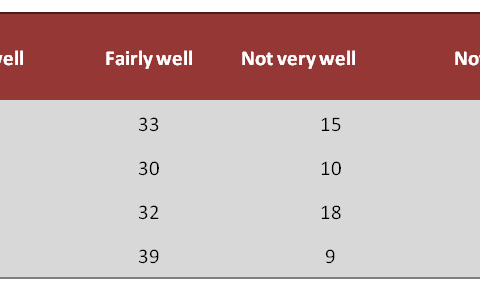

48 Figure 7: Organisations’ approach to employee wellbeing (percent of respondents) Source: Absence Management Report, CIPD, 2016 Note: Figures in tables have been rounded to the nearest percentage point. Because of rounding, percentages may not total 100 Another challenge is the lack of awareness around mental health problems within the organisation. The acknowledged stigma around discussing mental health issues means that organisations are likely to underestimate the number of employees with mental health problems and therefore underestimate its importance to the organisation. This is explored further in challenge themes 2 and 3. Those organisations that are starting to see mental health as a priority recognise that it is important for recruiting and retaining the talent of the future, and that good mental health and wellbeing is linked to strong performance. Quotes taken from Deloitte interviews with wellbeing teams across a range of companies to support the development of the Mind Workplace Wellbeing Index 0 20 40 60 80 100 Employee wellbeing is only a focus in our business when things are going well Employee wellbeing is on senior leaders agenda Employee wellbeing is taken into consideration in business decisions To a great extent To a moderate extent To a little extent Not at all 11% 34% 37% 19% 16% 27% 37% 19% 2% 13% 32% 52% “We’re increasingly competing for a smaller number of younger people… who are more inclined toward talking about their emotional and physical state.” Professional services company “We’ve done our own employee engagement surveys and it shows that wellbeing is positively correlated with overall engagement.” Manufacturing company 15 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Challenge theme 2: Mental health policies are reactive, driven by staff events or experience, and not proactive and preventative Employers are increasingly identifying mental health conditions within their workforce. Historically, action to improve the management of and support for employees with poor mental health was often only taken by employers following an internal or external trigger such as an employee’s mental health incident. Reactive mental health actions are those taken in response to an incident, such as increased reporting of poor levels of mental health in the organisation or following an individual case. In interviews with HR professionals across UK firms, many explained that often actions were taken after a highly personal or emotional case for change, rather than an objective, data-driven view of the impacts of workplace wellbeing on business performance . This is supported by data from CIPD, which shows that 61 per cent of organisations’ approach to employee wellbeing is much more reactive than proactive.

49 Figure 8: Organisations’ approach to workplace mental health and wellbeing “In 2007, I experienced a period of significant depression. It meant me taking two months off work, and it changed forever how I and Deloitte see and respond to colleagues with mental health difficulties. Once I had admitted my depression to senior partners, I thought my career would be over. But despite all my fears to the contrary, my colleagues reacted to my depression with unfaltering kindness and common sense. This allowed me to rest and recover in the same way that someone would who had a physical illness like a broken leg or a bad back. When I returned to work on a graduated return, the positive way the company treated me meant that I felt even more engaged and energised with Deloitte than before, which meant I was more productive than ever. I was made to feel valued and given time and support to get back to firing on all cylinders. Even without knowing the figures, this made the business case for investing in staff wellbeing crystal clear to me. Now I wish I’d spoken up earlier, so I could have got support at an earlier stage, before falling off the edge. My experience made me want to open the way for others in the early stages of depression – or managing someone in that situation – to talk openly.” John Binns, Deloitte

• Senior leader with lived experience galvanises support

• Clear external trigger or regulatory change

• Quantification of stress, absenteeism, presenteeism Reactive / emotional Proactive / data-driven Source: Deloitte interviews with wellbeing teams across UK companies 16 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Quotes taken from Deloitte interviews with wellbeing teams across a range of companies to support the development of the Mind Workplace Wellbeing Index “We know presenteeism is a problem, we just don’t know how to measure it.” Large manufacturing company Challenge theme 3: Lack of insight around current performance (including recruitment, retention and presenteeism) A lack of clear data around the impact of mental health on an organisation is a key challenge. Measuring workplace wellbeing and its impact on business performance is not easy. Due to the stigma associated with mental health, conditions and incidents tend to be under-reported and reasons for absence not given. Additionally, there is no clear consensus on how to properly measure presenteeism, defined earlier in this report as the loss in productivity that occurs when employees come to work but function at less than full capacity because of ill health. Despite these challenges, there are reasons to be hopeful. Expert organisations are beginning to weigh in to reduce the burden on employers who may have little to no expertise around wellbeing and its measurement. In 2013, the Government launched a workplace wellbeing tool to help employers work out the costs of poor employee health to their organisation and create a business case for taking action.

50 The Time to Change campaign introduced the highly oversubscribed free Organisational Health checks – an audit process and tool to help employers identify key gaps in workplace wellbeing provision.

51 17 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Challenge theme 4: Poor evidence base to measure return on investment of wellbeing strategies Measuring the return on investment (ROI) for workplace mental wellbeing initiatives poses a barrier to incentivising companies to invest. In our conversations with employers, there were no employers who had a plan for or the ability to measure the return on investment within workplace wellbeing. In addition to the difficulty of collecting data on ROI, results around ROI measurement are mixed. For example, an often-referenced Harvard meta analysis reporting a clear ROI on medical costs has recently been challenged on base of the validity of its methodology data according to an article in Health Affairs.

52 In addition, the comprehensive 2013 RAND Employer Survey on Wellness Programme Effectiveness across 60,000 US staff showed that wellness programmes were having only modest, if any, effect on healthcare spend.

53 Perhaps due to the lack of positive evidence, we tend to see relatively few employers actually taking on measurements of wellbeing. For example, whilst 100 per cent of US employers providing wellbeing services to their employees expressed confidence that their activities reduced absenteeism and health-related productivity losses, only 50 per cent had actually evaluated their impact. Furthermore, only two per cent reported actual savings estimates.

54 “We would really like to understand the business case for talking about mental health.” Large manufacturing company “Any investment we make needs a return, otherwise why are we doing it?” Large conglomerate company Quotes taken from Deloitte interviews with wellbeing teams across a range of companies to support the development of the Mind Workplace Wellbeing Index 18 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Source: Deloitte interviews with wellbeing teams across UK companies Quotes taken from Deloitte interviews with wellbeing teams across a range of companies to support the development of the Mind Workplace Wellbeing Index “We don’t really know how to improve.” Large consumer goods company “We’d like to invest in a wider preventative agenda, but we don’t know where to focus.” Large consumer goods company Challenge theme 5: Lack of collective knowledge around best practice Organisations vary in their level of engagement with mental health workplace wellbeing (see Figure 9). Some are more advanced, understanding its role in reaching peak organisational performance, and investing in the area as a strategic priority. However, when speaking with these organisations, regardless of their stage, all expressed an interest in understanding what best practice looks like, including those already considered best practice. This collective lack of information acts as a barrier to action, as we will explore in the implementation life cycle.: Organisational engagement with workplace mental health and wellbeing Level Basic Intermediate Advanced Best practice Motivation Risk mitigation and legal compliance Reactive case management Employee attraction and retention High-performance, inclusive workforce Reach Individuals in need Individuals/managers Wider workforce All employees Measurement None or basic Tracking against KPIs Clear business case Cost-benfit analysis Policy None or very basic Basic Comprehensive Strategic priority Workplace mental health and wellbeing engagement curve 19 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Collective actions for stakeholders Workplace mental wellbeing is at a tipping point, a “magic moment when an idea, trend or social behaviour crosses a threshold, tips, and spreads like wildfire”.

55 This trend is similar to that of corporate responsibility in the mid-1990s. Following in the footsteps of pioneers such as the food company Ben & Jerry’s, who in 1988 commissioned a ‘social auditor’ to work with staff, suppliers and the community to report on the social impact of their business. By 2002, over a decade later, 45 per cent of Fortune 250 companies published a form of CR report.

56 CR has thus moved from being a nice-to-have to a topic that is far more strategic with companies recognising the need for it to be embedded in day-to-day business operations. It is also increasingly being seen as an integral part of a company’s brand, relevant for employee recruitment, attraction, engagement and retention, as well as commercialisation of their products. Similarly, the rate of change in how employers think about workplace mental health and wellbeing will continue to accelerate driven by stronger awareness of mental health in the UK population and a growing recognition of the surrounding issues through sector leadership. However, to really deliver on the promise of these trends, collective action and engagement from employees, employers and society is required to overcome implementation barriers. Successfully implementing a workplace mental health and wellbeing improvement strategy requires organisations to overcome the challenges highlighted in the previous chapters of this report. It requires employers to take responsibility for creating a culture of awareness and support of employee mental health. illustrates the required continuum of pivotal actions for employers along the implementation cycle for workplace wellbeing programmes: The implementation life cycle for workplace wellbeing programmes Source: Deloitte research and analysis, 2017 Take stock and monitor performance Create buy-in for the case for change and investment Implement key initiatives Evaluate programmes and promote success Get mental health and wellbeing on the agenda Action for employers 20 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Key actions for employers include: Get workplace mental health and wellbeing on the agenda Moving towards a corporate culture of proactive, preventative management of workplace wellbeing (challenges 1 and 2) requires organisations to recognise the value of parity of esteem between mental and physical health in the workplace and to manage internal as well as external conversations and communications accordingly. For many organisations an important enabler for this has been the rising number of health and wellbeing leads in larger companies. Allocating a post dedicated to mental wellbeing can be an important and visible step in showing that the company is dedicated to taking action. Other actions could be developing a wellbeing framework or making an executive level statement on the corporate commitment to employee mental wellbeing, such as signing the Time to Change corporate pledge.

57 The desired output of this step is for workplace wellbeing to be on the organisational agenda and both supported and prioritised by senior leadership. This is essential as, whilst many organisations and individuals hope for their employees to have a good working environment conductive to mental health and wellbeing, operational demands can take over. Creating a culture where supporting mental wellbeing is prioritised enables the case for change to have a long-lasting impact. Take stock and monitor performance A critical requirement in support of the case for increasing awareness of mental health in the workforce in an organisation, is to develop and monitor key performance indicators (challenge theme 3). Making use of tools such as Mind’s Workplace Wellbeing Index (see Case study 1) or the Business in the Community and Public Health England Mental Health Toolkit for employers can help organisations to track quantifiable measures (e.g. presenteeism as well as absenteeism) both at baseline and over time.

58, 59 Moreover, continuously evaluating the impact of workplace wellbeing interventions and how they impact key performance indicators over time is crucial to demonstrating a return on investment for workplace mental wellbeing initiatives and generating continued momentum around interventions (challenge theme 4).

Case study 1: The Mind Workplace Wellbeing Index The Mind Workplace Wellbeing Index is designed to help employers to better understand how to support the mental health of their workforce. Deloitte supported Mind by conducting interviews with organisations across the UK to better understand their workplace wellbeing needs. These interviews highlighted that measuring baseline performance in terms of workplace wellbeing was key to understanding its importance, creating a case for change, and measuring progress over time. As a result Mind developed the Index. It is designed to be a major catalyst for change, as the Stonewall Equality Index was for the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community (see Case study 4).

60 Launched in September 2016, the Index aims to help overcome a number of the key barriers to change:

• creating an evidence base of best practice

• conducting an ROI evaluation to demonstrate that investing in employee mental health has a positive impact on the bottom line

• breaking down mental health stigma in UK workplaces

• generating new data on key trends across different sectors and sizes of organisations. Surveys are given to employees as well as central teams in order to understand what policies and practices to support mental health are present. Employers then receive an assessment report outlining key gaps and recommendations for improvement. Employers are ranked as bronze, silver or gold. The Workplace Wellbeing Index first year results are launched end of March 2017. 21 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Create buy-in for the case for change and investment Another important step in tackling workplace mental health is the development of a business case to support investment. Many organisations get stuck at this step. The development of a strong evidence base through monitoring of performance can make the case to prioritise improving employee mental health (challenge theme 1) and reduce the likelihood of action only being taken in a reactive manner (challenge theme 2). Furthermore it is a pre-requisite to inform changes in policy and organisational design. One way to combat this issue is to work with a progressive occupational health (OH) provider. The attitudes of OH providers are changing, as they increasingly look to become strategic partners to their clients and help drive internal change. Forward thinking OH providers are moving from managing sickness absence to demonstrating the ROI to be gained by improving health and wellbeing, designing pro-active preventative solutions, finding ways to increase employee resilience and tailoring workplace health programmes to the needs of their client’s staff. A key barrier to making the case for change comes from the lack of clear data on the ROI on workplace mental wellbeing initiatives. The EDF Engergy case study shows the power of such data (see Case study 2). Good case studies or networking with companies with shared employee characteristics or attitudes can provide the arguments necessary to develop a strong case for change. Implement key initiatives adapted for specific workforce challenges and demographics Having successfully argued the case for change and improved investment, it is important to find the right initiatives to fill the organisational gaps and achieve the required outcomes. Whilst some organisations may struggle to define what best practice looks like (challenge theme 5), taking even small, timely and measurable actions is likely to have a positive impact.

Case study 2: EDF Energy Understanding baseline performance and creating a case for change: A workplace audit showed that the company was losing around £1.4 million in productivity each year as a result of mental ill health among its employees. Implementing key initiatives: EDF Energy’s Employee Support Programme (ESP), a partnership between occupational health and a psychology service5, was developed in consultation with all the company’s stakeholders, including the EDF Energy Executive, branch managing directors, OH, trade unions and over 500 members of staff. A cognitive behavioural therapy programme was rolled out to employees across the company’s 100 sites, providing fast access to treatment and advice for mental health difficulties. A related training programme taught 1,000 managers to recognise mental ill health amongst staff and minimise its adverse effects. Evaluating programme success: Improved productivity saved the business an estimated £228,000 per year. Staff morale also improved: employees who claimed to be ‘happy in my job’ increased from 36 per cent to 68 per cent, and the Health and Safety Executive awarded the programme Beacon of Excellence status.

61 However, differences in employee needs will require different intervention strategies and reliance on one strategy alone is unlikely to yield significant results. The Deloitte case study shows a range of targeted interventions in a mental health and wellbeing strategy (see Case study 3). 22 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Further examples of the types of interventions that could be used to address employee needs, and organisational characteristics include:

• mental health anti-stigma and awareness-raising activities

• providing training to employees on mental health awareness and how to manage their own mental health

• training for managers on workplace wellbeing

• setting up a network of mental health champions or coaches in the workplace

• purchasing an employee assistance programme that gives employees access to telephone or face-to-face counselling when required, and ensuring it is well promoted and uptake is monitored • creating a best-practice mental health policy.

Case study 3: Implementation of mental health and wellbeing strategies at Deloitte Deloitte has increased the focus of its mental health and wellbeing activities on prevention, and since signing the Time to Change pledge in 2013, is using metrics to create demonstrable change. This includes both increased engagement with external initiatives and partners and internal strategies to create a culture of transparency and awareness around mental health within the organisation. Deloitte has publicly shown its belief in maintaining the public conversation around mental health, with a number of different engagements with external partners including:

• working with Mind to increase disclosure of mental health issues and participating in the inaugural Mind Workplace Wellbeing Index has helped to gain real insight into how our actions are making an impact for our people

• Deloitte is a member of the City Mental Health Alliance (CMHA) and in May 2016, hosted a CMHA supported panel discussion on mental health in black, Asian and minority ethnic communities, led by Deloitte’s multicultural network, one of ten diversity networks in the firm.

• participating in the citywide ‘This is Me’ campaign to reduce stigma and encourage open conversations about mental health.63 This campaign is based on a highly successful campaign developed by one firm who have successfully run it for a number of years and have seen a significant change in the culture and way mental health is talked about in the organisation. The campaign focuses on anxiety and depression because data demonstrates these are the most prevalent mental health conditions at Deloitte, and that encouraging early disclosure helps people get access to the support they need quickly. A short film on the Deloitte intranet shows individuals from different grades and areas of expertise talking about their experience of ill mental health. It has been viewed over 11,300 times so far, and the participants have received unprompted emails from colleagues across the firm thanking them for sharing their experiences and saying how inspirational they are in September 2016, Deloitte hosted a conference for Unwired, called Wellness 16, which explored mind, body and spirit and included a presentation on Deloitte’s approach to health and wellbeing.

64 23 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Evaluate programmes and communicate successes Programme learning and knowledge sharing are essential for any successful organisation and this is even more important in an area such as workplace mental health and wellbeing where collective knowledge is in its infancy. To be successful all programmes should be iterative with results evaluated and lessons embedded. Ideally this would include a formal assessment of changes in staffs’ mental and physical health. However, this stage can also be informal – as one interviewee during our work with Mind stated: “Rather than calculating numbers, we got further buy-in and investment by sharing early benefits”. One of the biggest single barriers to development in this space is a lack of awareness of what works. If a programme has been demonstrably successful for an employer, either overall or for a particular sub-segment of employees, other employers would benefit from hearing about it and the promotion of the programme can also be of value to the organisation in raising their profile as a progressive employer. In addition, as noted earlier in this report, there is often a difference between how leadership perceive internal mental health programmes and the experience and knowledge of an organisation’s employees. Reduction of these perception gaps requires following-up on the implementation of new initiative by tracking of internal knowledge levels and increasing communication of successful programmes.

Case study 3: Implementation of mental health and wellbeing strategies at Deloitte (continued) Internal measures taken include:

• changing the components of the employee assistance programme and creating an ‘Advice Line’ in response to feedback collected from employees. This has led to an increase in the number of people using the services and receiving help with problems earlier, including support in adapting individuals’ work surroundings

• in 2014 Deloitte launched its focus on agile working, including the introduction of its award winning Time Out programme (enabling its employees to take one month’s unpaid leave each year, at a time that suits the employee and the business). The firm has worked hard to ensure that its culture reflects its agile working principles – namely, trust and respect, open and honest communication and judging solely on output

• in 2016 Deloitte increased its focus on prevention, by ensuring our people have access to the right mental health resilience tools. Deloitte continues to deliver resilience workshops across different grades and encourage early disclosure across our business

• appointing mental health champions across the different sectors of the firm to ensure that employees get the right mental health support when needed. 24 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Successful and sustained change requires that employees understand their own state of mental health and wellbeing as well as recognising and supporting colleagues. As part of a culture of awareness of the importance of mental health employees need to: Engage in their own health Employees should take responsibility for improving their own mental health literacy by accessing available information, learning about options of support and actively participating in strategies that promote both mental and physical wellbeing in accordance with individual needs and preferences. Increasingly digital health and apps can make engagement in an individual’s mental health easier. For example Soma Analytics have developed an application which measures work-related stress. It uses the sensors in people’s smartphones to identify behavioural changes, such as sleep quality, emotion in voice and physical activity that signal they are at a risk of work-related mental ill health. The app enables both individual employees and HR teams in organisations to monitor wellbeing and increase resilience to work-related stress both individually and through a dashboard function.

65 Speak up Employees can contribute to achieving better overall workplace wellbeing by getting actively involved in discussions on mental health and wellbeing in the workplace, as well as inputting to the design, management and performance measurement of their employer’s wellbeing strategies and action plans. These actions could range from participating in an employee survey on mental health to volunteering as a mental health champion in the workplace or sharing personal stories so others feel empowered in their own personal circumstances. Support colleagues In order to sustain a culture of openness and transparency around mental health and wellbeing, employees should listen to and support team members with mental health and wellbeing concerns at both peer level and as line managers. Employees can support improvements in overall workplace mental wellbeing by ensuring they are aware of both how to raise concerns about colleagues and also what actions to support co-workers they can reasonably take. There is no one-size fits all solution, so knowing what options are available, and taking a flexible approach, is important. Society and the state should support collaboration with corporate employers to improve workplace mental health. Stakeholders across the third sector, occupational health providers and policymakers can contribute to alleviating the pressures resulting from poor workplace wellbeing by taking the following actions: Invest in research and an improved evidence base The evidence base regarding ROI for mental health interventions is on average weaker than for many other health conditions. As a new area, the evidence base for workplace mental wellbeing interventions is currently even further limited. However, even if ROI calculation is challenging, it is possible to develop a tailored scenario based approach to show what the cost of getting it wrong is. Further research and methodology development should be a priority area for mental health advocates, charities and OH providers to address. Form strategic partnerships Engaging in partnerships with other stakeholders and similar companies will allow organisations to learn from the evidence of best practice elsewhere. Expert organisations in the third sector should seek to enhance their impact by entering into partnerships with corporates, such as partnering with OH or health app providers. Action for employees Actions for key stakeholder across society and the state 25 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing OH providers have a particularly important role to play as strategic partners to organisations aiming to improve their employees’ mental health. As strategic partners, OH can be instrumental in designing preventative solutions and tailoring workplace health programmes to increase employee resilience. Indeed, OH providers’ leadership, as drivers of change and knowledge sharing, is essential for providing the requisite momentum for rapid change. Investing in getting this right represents a significant business opportunity for OH. Support of workplace wellbeing initiatives In the past couple of years there has been a welcome rise in the number of mental health initiatives in the workplace, including the Time to Change employers pledge.

66 Governmental support has been instrumental in the wider Time to Change anti-stigma campaign, that has been successful at breaking stigma and raising general awareness of mental health issues. However, as mentioned in the first part of this report, there is much work still to do on mental health in the workplace. To raise awareness of the issues of workplace wellbeing, governmental support for mental health issues needs to continue both inside and outside of the workplace. Get the incentives right Policymakers need to focus on policies that provide aligned incentives to encourage companies to take charge of employees’ mental health and promote actions that improve mental wellbeing. Historically, regulation has been a powerful change agent in the adoption of positive occupational health practices. A specific example of this is in the adoption of improved LGBT work practices, as demonstrated in the Stonewall case study, where Stonewall was able to use the launch of a new regulation in 2003 to create momentum among employers in evaluation of their workplaces relative to peers (see Case study 4).

67 Government policy has increasingly called out the responsibility of employers to safeguard the mental health of their employees, but firm incentives have not, as yet, been implemented. Action to extend incentives for employers who provide effective NICE recommended workplace health programmes, such as those recommended in the March 2017 guidance on healthy workplaces, including providing tax relief, would be a significant catalyst for change.

68 However, any policies adopted should be underpinned by evidence regarding the outcomes of initiatives and at the same time allow for agile adoption in the interest of individual employees, recognising diverse organisational needs and adapt to shifting preferences in society. Case study 4: Stonewall Workplace Equality Index Following new employment equality regulations in 2003, Stonewall, Britain’s leading LGBT equality charity was first approached by corporates seeking their advice and expertise. With interest in the area rising, they were able to launch a corporate equality index in 2004. Membership and momentum grew significantly over the next decade from initial cold calls to 100 non-member employers in 2004 to 700 members in 2015. Today, Stonewall regularly collects around 50,000 employee responses at 400 employers and offers year-round support and feedback. The model is widely considered to have had a very positive impact on the LGBT community through improved transparency and greater awareness of good initiatives. In addition to improved outcomes for a minority group the model has also had a positive impact on charitable income for Stonewall. 26 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing Future developments Over the past couple of years we have seen an increase in prominent advocates, the launch of mental health and wellbeing tools, new health and wellbeing roles created in corporates, and a rise of workplace mental health and wellbeing in the commercial narrative. After the launch of many new initiatives by stakeholders in 2016, already in 2017 we have seen the Prime Minister’s January speech on mental health including the announcement of an independent report on companies’ work to support mental health and promote best practice. The planned government report will further focus on how best to learn from trailblazer employers, as well as offering tools to assist with employee wellbeing and mental health. As these actions continue, the prominence of wellbeing on the corporate talent and social responsibility agenda will grow. However, despite the significant number of drivers, considering progress to date, it will still be a number of years before workplace mental wellbeing takes a prominent role and becomes a major strand of good corporate responsibility. Moreover, the rate of adoption will continue to depend on the attitudes of individual companies. Firms with a greater competition for talent and more vocal and engaged leadership will remain an important leader in this respect. We believe there are three factors that will determine how quickly the potential of this area is realised for the benefit of employees, employers and society:

• addressing the lack of consistent knowledge of what works and the quantification of investment returns. Collective action in this space could rapidly increase the actions taken by employers and should be a priority area for mental health advocates, charities and occupational health providers to address

• the importance for organisations of being able to demonstrate credentials in supporting employees’ mental health and wellbeing. This area will be progressively more important as employees increasingly look at best practice in this space when making competitive employment decisions. Under a buoyant economic scenario an increasingly competitive workplace will require companies to address these issues to attract the best talent

• the power of incentive to drive change. Policy changes that support employers to invest in their employee’s wellbeing should be a priority for policymakers. This report makes a clear and compelling case for improving the profile of employee mental health and wellbeing, including the societal benefits that could ensue. By investing in improved support for employee mental health, we believe that the employee gains; the employer gains; and the economy gains. We expect that by 2025 employee mental wellbeing will be a significantly more common theme in corporate reporting and that the actions that have helped make this a reality will have been promoted by all interested stakeholders. 27 At a tipping point? | Workplace mental health and wellbeing

1. Wellbeing – Why it matters to health policy, Department of Health, 2014. See also: https://www.gov.uk/government/ uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/277566/ Narrative__January_2014_.pdf

2. How to improve your mental wellbeing, Mind Org, 2013. See also: http://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/tips-foreveryday-living/wellbeing/#.WL-yP2-GOM8

3. Mental health: a state of well-being, WHO, 2014. See also: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/

4. Stress at the workplace, WHO, 2017. See also: http://www. who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en/

5. Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households in Great Britain (2000), Office for National Statistics, 2002. See also http://webarchive.nationalarchives. gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/ Publications/PublicationsStatistics/DH_4019414

6. UK Labour Market 2016, Office for National Statistics, 2016. See also: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/ employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/ april2016

7. Work related stress, anxiety and depression statistics in Great Britain 2016, Health and Safety Executive, 2016. See Also: http://www.hse.gov.uk/STATISTICS/causdis/stress/ stress.pdfz

8. Ibid.

9. Stressed out staff feel unsupported at work, Mind, 2014. See also: http://www.mind.org.uk/news-campaigns/news/ stressed-out-staff-feel-unsupported-at-work-says-mind/#. WKSbIG-LTIU

10. National Employee Mental Wellbeing Survey, Business in the Community- The Prince’s Responsible Business Network, 2016. See also: http://wellbeing.bitc.org.uk/wellbeingsurvey

11. Mental Health at Work Report 2016, Business in the Community- The Prince’s Responsible Business Network, 2016. See also: http://wellbeing.bitc.org.uk/system/files/ research/bitc_mental_health_at_work.pdf

12. Workplace stressors & health outcomes: Health policy for the workplace, Behavioral Science and Policy Association, 2015. See also: https://behavioralpolicy.org/article/ workplace-stressors-health-outcomes/

13. Attitudes to Mental Illness 2013 Research Report, TNS BMRB, 2014. See also: https://www.time-to-change.org.uk/sites/ default/files/121168_Attitudes_to_mental_illness_2013_ report.pdf

14. Mental Health at Work Report 2016, Business in the Community- The Prince’s Responsible Business Network, 2016. See also: http://wellbeing.bitc.org.uk/system/files/ research/bitc_mental_health_at_work.pdf

15. The effects of divorce and separation on mental health in a national UK birth cohort, Cambridge University, 1997. See also: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ psychological-medicine/article/div-classtitlethe-effects-ofdivorce-and-separation-on-mental-health-in-a-national-ukbirth-cohortdiv/0E5ACBCC208189F7105935BA9E5686D5

16. Mental Health: Poverty, Ethnicity and Family Breakdown Interim Policy Briefing, The Centre for Social Justice, 2011. See also: http://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/library/ mental-health-poverty-ethnicity-family-breakdown-interimpolicy-briefing

17. Work related stress, anxiety and depression statistics in Great Britain 2016, Health and Safety Executive, 2016. See also: http://www.hse.gov.uk/STATISTICS/causdis/stress/ stress.pdf

18. Mental Health at Work: Developing the business case, The Sainsbury Centre for Mental health, 2007. See also: http:// www.mentalhealthpromotion.net/resources/mental_health_ at_work_developing_the_business_case.pdf