Time to Change is a campaign to end the stigma and discrimination that people with mental health problems face in England. It is run by the charities Mind and Rethink Mental Illness, with funding from the Department of Health, Comic Relief and the Big Lottery Fund. Since Time to Change began in 2007 more than two million members of the public have improved attitudes towards people with mental health problems, and more people than ever are able to be open about their mental health problems.

Time to Change aims to empower people to challenge stigma and speak openly about their own mental health experiences, as well as changing the attitudes and behaviour of the wider public. Work with organisations to reduce mental health stigma and discrimination in the workplace has been a key focus for Time to Change. This includes providing support for HR professionals, managers and employees; as well as working with organisations to sign the Time to Change Employer Pledge.

The Pledge is an inspirational commitment made by an employer to tackle mental health stigma and discrimination in their workplace. Each pledge is backed up by a bespoke action plan detailing the tangible activity that will be undertaken to deliver on this commitment.

This report has been written by independent consultants, Dr Helen Ferris Baker and Tom Oxley and produced by the Time To Change Employers Team.

For further information, please contact the Time to Change team at [email protected]

Time to Change conducted a series of Organisational Healthchecks between 2013 and 2015, designed to review the employee experience of mental health in different workplaces. This report brings together evidence and employer recommendations from those Healthchecks, and draws from the experiences of 15,000 employees across 46 organisations in England. Of the 46 participating organisations, 29 were public sector organisations, eight were private sector organisations and nine were voluntary sector organisations.

Public sector employers included local authorities, NHS Trusts, police forces, government departments, universities and student unions, prison services and a political party. Private sector employers included financial services, communication organisations, utility companies and various health providers. Voluntary sector employers included national charities and advocacy services.

One of the main aims of this report is to inform employers about employees’ experience of mental health in a variety of workplaces. Through sharing examples, the report illustrates good practices in creating a culture where staff feels able to be open about their mental health across the public, private and charity sectors. This report also considers different responsibilities of senior leaders, Human Resources and Occupational Health professionals in supporting employees with mental health problems. Recommendations were made to participating organisations about how they could improve, based on their employees’ feedback. These have been summarised in the final section. These recommendations include changes that organisations can make around policy, practices and the working environment. They outline key stages that will help any organisation assess their own progression towards tackling stigma and supporting employees with mental health problems.

About this report

Each Time to Change Organisational Healthcheck had four objectives:

- To help organisations identify gaps between the aspirations of their mental health-related policies, and actual practice and culture

- To highlight discrepancies between the perceptions of management and those of employees with mental health problems about how the latter are supported.

- To improve the ability of managers to support people with mental health problems.

- To facilitate practical steps which organisations can take to close these gaps.

All Healthchecks were voluntary and completed by independent consultants, supervised by Time to Change. Each Healthcheck comprised of three stages:

- A review of HR information provided by a range of employers (including policies and processes).

- Confidential, in-depth interviews with employees (all of whom had lived experience of mental health problems).

- A confidential staff survey with consistent questions across different organisations (open to all employees)

Across the Healthchecks, one of the main recommendations made by both respondents and Healthcheck consultants was that organisations needed a clear ongoing internal campaign and plan to ensure that conversations about mental health continued beyond the involvement of Time to Change. As a result of this recommendation, we ask all organisations signing the Time to Change Employer Pledge to fill in an action plan. The plan is designed to help them to structure their work in this area and create a long-term approach to tackle mental health stigma and discrimination within their workplace.

ABOUT THE SURVEY

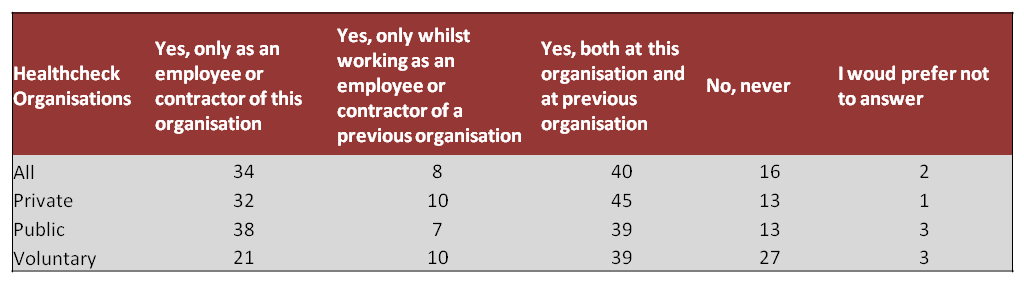

The findings in this report come from both the Healthcheck staff surveys and interviews with employees willing to talk about the support they had received around mental health in work. 82% of respondents (approximately 12,000 people) reported experiencing stress, low mood or mental health problems whilst in employment.

Question 1: Have you ever experienced stress, low mood or mental health problems while in employment?

The respondents represented a range of ages, although the majority of employees were aged between 25 and 54. 67% of respondents were female and 33% were male.

MENTAL HEALTH IN THE WORKPLACE

The Healthcheck surveys aimed to understand gaps between policy and practice; differing opinions between managers and employees around support provided; management’s ability to provide support; and practical steps which can be taken to close these gaps. People with their own experience of mental health problems were actively encouraged to participate and people also had an opportunity to offer qualitative comments. The key findings, including themes from the qualitative data, have been included below.

Impact of poor mental health in the workplace

37% of employees reported having had to take time off work because of stress, low mood or poor mental health, 68% reported to having gone into work at some point when experiencing poor mental health.

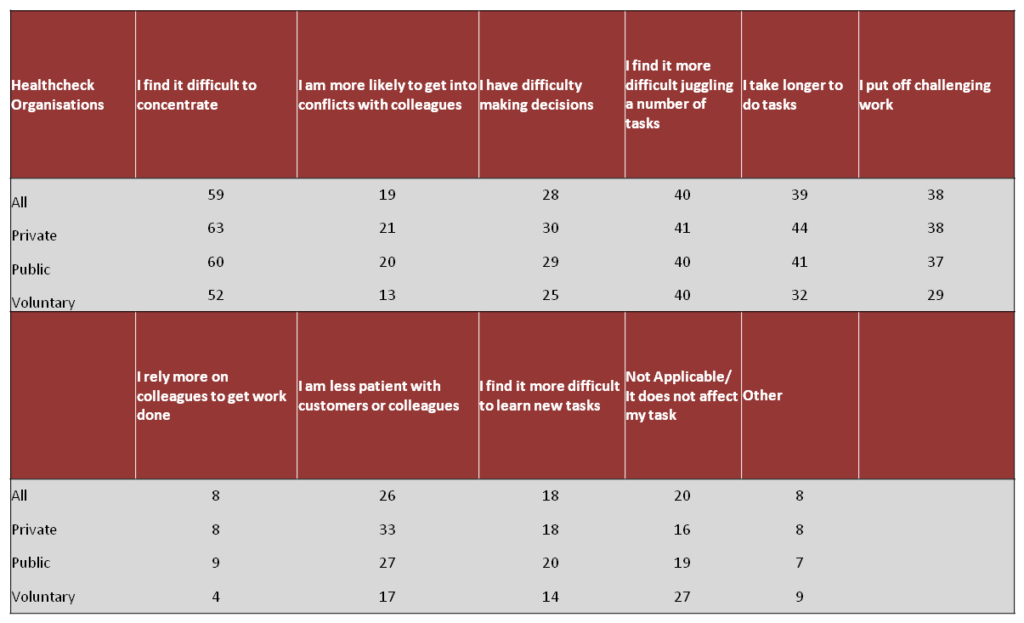

59% of all respondents said poor mental health was a primary factor that impacted on their ability to concentrate at work. 40% of respondents reported that they found it difficult to juggle a number of tasks, took longer to complete tasks (39%) and that they tended to put off challenging work (38%).

Question 3: How often have you gone into work when experiencing poor mental health (for example stress, anxiety, depression or other?)

Question 4: In which ways, if any, does your poor mental health in the workplace affect your performance?

These figures suggest that many employees go into work when experiencing poor mental health and this impacts on their performance in different ways. A number of respondents across the Healthchecks reported that they often felt pressure to come to work and some were concerned about how this might impact their employment prospects.

Although organisations need to pay attention to reasons given for sickness absence, respondents to these Healthchecks confirm that presenteeism is the more urgent issue and potentially an area of consideration for policy change. Presenteeism occurs when employees come to work, but are unable to carry out their work duties for a number of reasons. A review by the Centre for Mental Health (2010)1 identified that the cost of presenteeism may exceed that for sickness absence.

Causes of poor mental health in the workplace

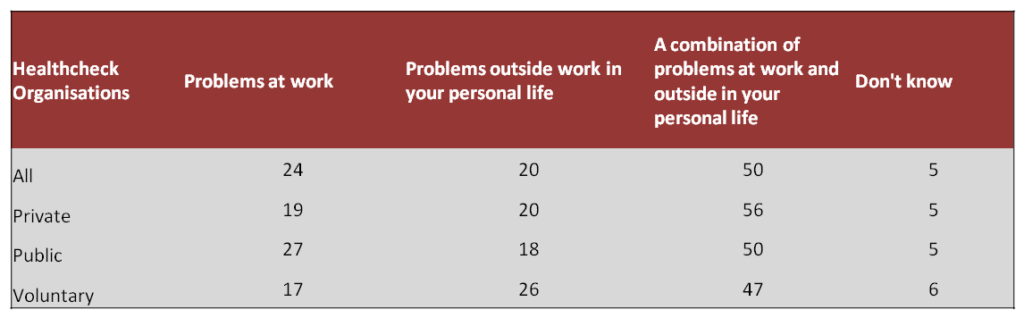

24% of respondents reported that their poor mental health was down to problems at work and 20% reported that it was a result of issues in their private life. Half of all respondents noted that poor mental health was a result of a combination of problems at work and in their personal life.

Question 15: Do you think that your moderate or poor mental health is the result of:

Employees within the public sector often reported workload and personal control as an issue which negatively impacted their mental health, more than employees from other sectors. The majority of respondents recognised the impact of both their work and personal lives upon their mental health. Across the Healthchecks respondents commented that it was almost impossible to clearly distinguish the influence of both work and personal issues when understanding the cause of their mental health problems. However, there was a repeated suggestion that work could trigger or exacerbate conditions.

MENTAL HEALTH SUPPORT AT WORK

Support provided to employees

57% of all employees were aware of mental health support that was available to them. When asked if employees knew where to find support tools or policies, around 50% of private sector employees reported they knew, compared to 70% of voluntary sector employees.

46% of respondents felt that they were confident in their manager being able to implement support tools but around a third were not (34%).

Out of those employees who sought support from their managers, 78% were provided with some help or a lot of help from their employer or manager to manage their work demands and mental health, but approximately 19% of respondents who sought support received none.

Across the Healthchecks there was a wide range of different support offered to employees. Many organisations offered access to Occupational Health or an Employee Assistance Programme providing access to counselling or other mental health support services. Many respondents reported variable experiences of support that was offered to them, dependent often on whom their line manager was. Support was also centred on changes to the individual rather than the organisation – which is indicative of a more reactive rather than preventative approach to mental health at work.

Question 11: Did you receive any support from your employer or manager to manage your mental health and the demands of your job?

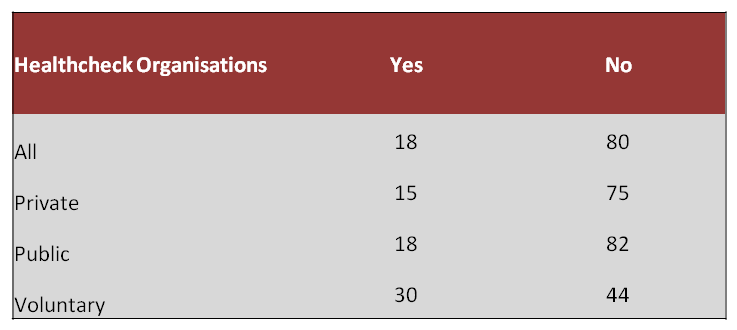

Out of the employees who sought support by disclosing to their manager or employer, 18% of respondents reported experiencing adverse treatment when asking for support around work demands and mental health problems. Examples of adverse treatment included discrimination, forced time-off, breaches of confidentiality, removal of important work tasks and other negative behaviour towards the individual.

Question 12. Did you experience any adverse treatment from your employer or manager as a result of disclosing stress or mental health problems?

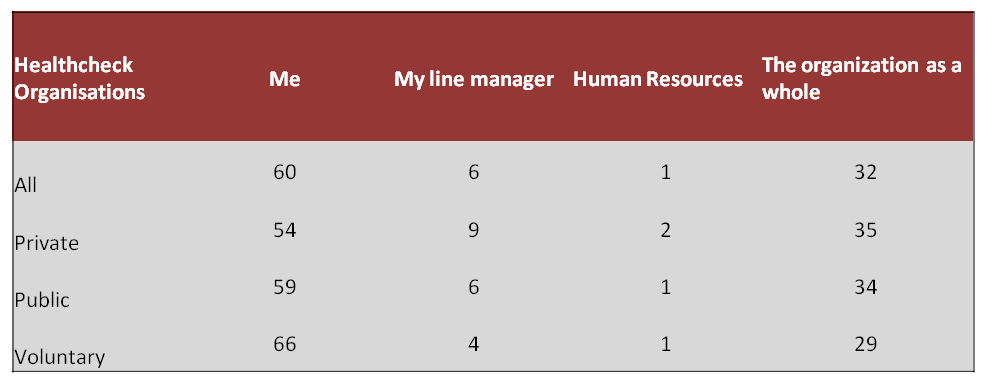

Responsibility for mental health and support provided to managers

Overall, 60% of respondents felt that they were responsible for their overall mental health and wellbeing at work, but 32% felt that the organisation as a whole was. 6% identified their line manager as being responsible. Respondents across the Healthchecks also reported that they felt their organisations had a responsibility to provide support for helping to manage mental health problems at work.

Question 19. Who do you consider is primarily responsible for your mental wellbeing in the workplace?

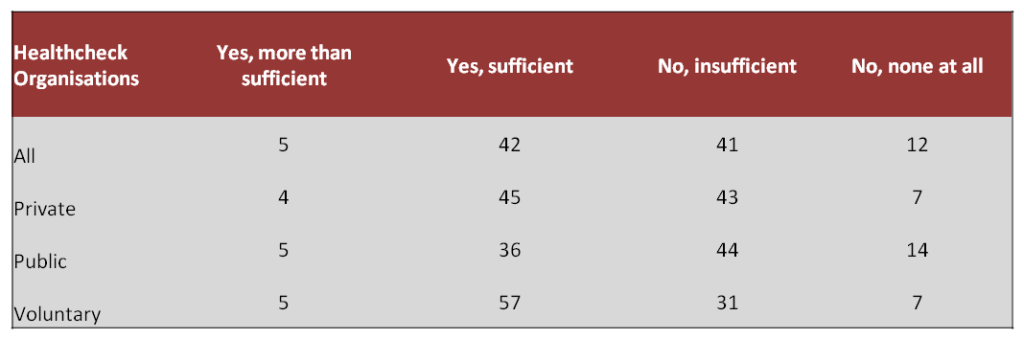

31% of respondents identified that they line manage people. Out of those managers, 79% felt confident in supporting people who they line manage with mental health problems. However 53% felt that they had been given insufficient information, support and guidance by the organisation on how to support team members with mental health problems. The majority of managers therefore appear confident in being able to provide support, but still feel as if they have not been provided with enough support themselves. There seems some discrepancy here; potentially managers as a group are feeling unsupported themselves, even if able to provide line management support to colleagues.

Those managers in the voluntary sector felt they had received better support and information with 62% recognising helpful resources that they had been given. Many respondents mentioned the need for better training about mental health, but also in general line management skills.

Question 30. Do you feel you have been given sufficient information and guidance from the organisation on how to support people you line manage that experience mental ill health?

OPEN DISCLOSURE AND DISCUSSION ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH IN THE WORKPLACE

Disclosing mental health problems

59% of employees working within the public or private sector thought that their employer or line manager would be supportive if they disclosed their mental health issue. Within the voluntary sector, this rose to 69%.

However, when respondents were asked if they had disclosed their mental health problems to their employer or manager, only 31% of employees had done so. This was replicated across the different sectors, illustrating a discrepancy between feeling supported to disclose and still not feeling able to actually talk to their manager. Some respondents reported that they feared discrimination upon disclosing e.g. creating career-limiting bias on their unofficial record – a fear which is perceived as a real threat for many employees.

Discussing mental health openly at work

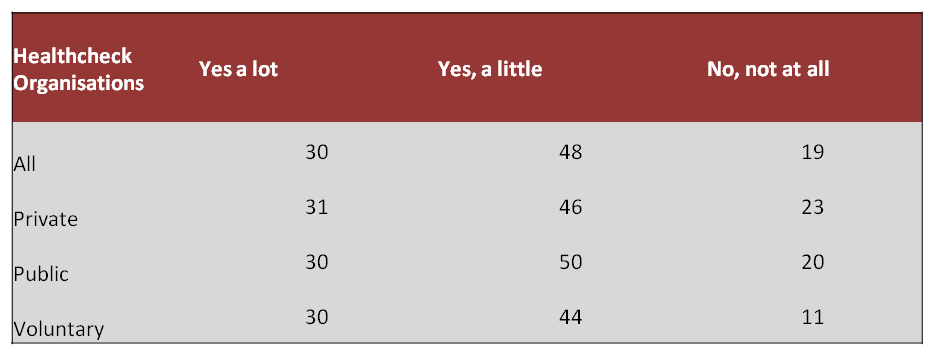

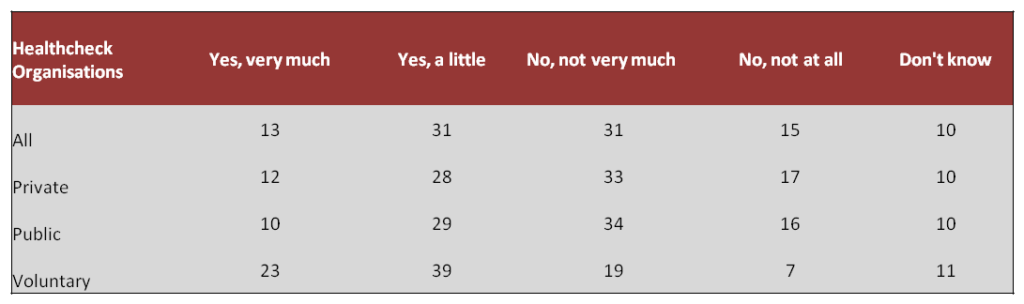

Across the Healthchecks, 46% of respondents thought that their organisation did not encourage staff to talk openly about mental health problems.

Question 16. In your opinion, does your organisation encourage staff to talk openly about mental health problems?

Within the voluntary sector, more respondents thought that their organisation did encourage staff to talk openly about mental health (62%), with employees in both the public and private sector reporting more could be done to encourage open dialogue.

Understanding organisational support for mental health at work

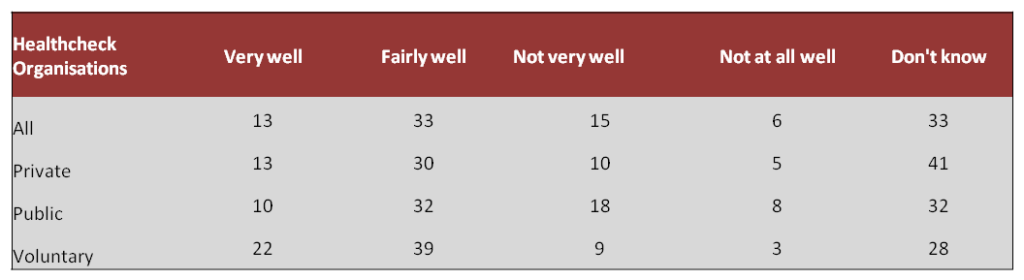

Many respondents, across all sectors, were unsure generally how well their organisation supports people with mental health issues (33%).

Despite many having mental health problems themselves, a large proportion of private sector employees (41%) did not feel able to answer ‘how well does your organisation support employees who experience mental health problems?’. Overall 33% of respondents described their organisation as supporting staff ‘fairly well’ when it came to mental health issues. The voluntary sector had the highest number of respondents identifying that their organisation supports their staff ‘very well’ when it comes to mental health issues (22%).

These figures further support another clear recommendation across the Healthchecks to develop clear ways of sharing best practice around how to support people with mental health problems.

Question 17. In your opinion, how well does your organisation support employees who experience mental health problems?

CONCLUSION FROM THE HEALTHCHECK SURVEYS

Overall the Healthchecks illustrated that poor mental health, low mood and stress at work are critical factors which impact wellbeing and productivity at work. Poor mental health impacts employees across all workplaces – yet those employees often remain at work when they are unwell.

When employees are experiencing poor mental health they find it difficult to concentrate, juggle work demands and complete more complex tasks. Work demands can be a direct cause of or trigger of poor mental health, though the original cause is often mixed with other factors. Evidently many employees feel supported and good practices are in place. However, many employees do not feel confident in disclosing their needs and potentially one in five people who have reported mental health problems to their employer have experienced adverse treatment. Discrimination is a perceived and real fear for many.

Many managers do not feel they have received enough guidance about how to manage and support employees struggling with their mental health.

The final Healthcheck objective was to determine what practical steps could be taken by organisations to improve support for people with poor mental health in the workplace. Respondents recommended both a continuing campaign to open up conversations about mental health and sharing best practice between colleagues, managers and across organisations to increase support for people with mental health problems.

Organisations still need to encourage open dialogue about mental health and communicate the support that is offered to employees, however, sometimes it simply isn’t getting through to the people who need it – at considerable cost to employee and employer.

THE STORIES BEHIND THE STATISTICS

Examples of good practice at varying levels of seniority

This section reflects the combined experiences across different organisations, drawing on interviews with employees with personal experience of mental health problems and the staff Healthcheck surveys.

Common themes from the responses and the interviews have been included. They illustrate good practice and are a guide to better performance for leaders, HR and Occupational Health professionals, and line managers.

Many of the best examples came from people who had experience of mental health problems and used it to help others – but personal experience was not a prerequisite to fair and understanding treatment.

Good practice: senior leaders

Leaders who get it right are confident in communicating about mental health in their workplace. They take responsibility to commit to cultural improvements, participate in training themselves, and break stigma about mental health and career progression.

Some top level leaders were open about their own experience of mental health problems which normalised the conversation and reduced stigma. They become role models for positive health management in their organisation and inspired other managers. In different organisations, activity began with a ‘statement of intent’ on mental health which cascaded through the organisation. This statement was the catalyst to genuine behaviour change that lived up to organisational values.

“So what I want is to get to the stage where we treat it with the same respect as other conditions and maybe even use work as part of the recovery.” Head of Occupational Health, private company

Good leaders understood that organisational resilience and good process helped manage staff as a strategic resource issue, especially at times of predictable organisation stress.

“They’re trying to raise awareness about this, and highlighting senior members of staff who disclose having mental health issues – and that it hasn’t stopped them progressing with their career.” Government department

Respected leaders acknowledged change was needed. They were open and prepared to embrace change to help all employees (including part time and volunteer staff) consistently. They desired a more sustainable ‘new norm’ about workload and long hours. They generated trust by demonstrating through their behaviours that people are the organisation’s most important asset.

Good practice: Human Resources and Occupational Health professionals

HR and Occupational Health performed best in terms of supporting those with mental health problems when their roles were clear (and regularly communicated) to managers and employees. HR and Occupational Health needed concerted communications support to achieve this.

“We want to do what is right, fair and practical. We can’t magic up a new job. But we can employ reasonable adjustments: change targets, change where they sit, offer alternative jobs.” Senior Manager, Financial Services

HR had trained specialists and worked to establish simple policies and processes which were reviewed by employees with experience of mental health problems, such as an employee network group. A positioning statement on mental health from a senior leader created a strong statement of intent, and a separate policy is not always required. However, in organisations leading the way in this area, guidance and support on mental health was integrated within other policies, e.g. Health and Safety, Wellbeing, People, Equality and Code of Conduct policies.

Absence and competency management were differentiated from mental health support. Postabsence procedures (e.g. return-to-work action plans) were robust. Reasonable adjustments were enforced and transferred between managers (where an individual’s line manager changed).

“My employer needs to be a little bit less afraid of things going wrong.” Public Sector

HR data on absence type was robust (it was all recorded for a start) and was available by department and by other protected characteristics. Such statistics were considered alongside staff survey information from mental health-specific questions. All feedback was acted upon – not just complaints.

Best practice showed HR or Occupational Health were responsible for adequate training and general awareness – from managers to self-care and proactive employee resilience. Training took many forms: induction, staff handbook, specialist supervision, intranet-hosted, lunch-and learn sessions.

“When the employee is medically well, work could be part of the solution.” Head of Occupational Health, Private Sector

Good Occupational Health teams have a swift and robust process in place to establish contact, and offer assistance, to individuals as soon as they become unwell or disclose.

HR facilitated employee support at many levels: Employee Assistance Programmes, in house counsellors, charity partnerships and return-to-work planning.

Employee mental health network groups set up with assistance from HR were particularly helpful for peer support and promotion of positive case studies about mental health support (not simply taking work away from people). Line manager groups were also helpful to share good practice.

Good practice: managers

Good managers didn’t try to do too much, and certainly didn’t try to be therapists. Instead they got the basics right: were conscious of the signs of poor mental health, clear on the support available and ‘checked in’ with the individual at appropriate times (e.g. one-to-ones).

They encouraged safe disclosure with their teams, researched conditions and invited ideas from staff with their own experience, thereby empowering employee-led ideas for adjustments.

“My manager said, ‘Let’s wait and see how long it takes. We’ll get you well again and work out everything from there’.” Financial

Managers with experience of mental illness were best equipped to help employees. Those showing empathy, compassion, and also clarity, fairness and consistency, were respected and kept valued talent at work.

They executed basic manager duties (1-to-1s, appraisals, wellbeing catch ups). They utilised return-to-work plans (and stuck to them) and also transferred notes (with permission) to future managers. Astute managers used HR policies flexibly in some cases, achieving loyalty in teams.

“If anything, work keeps me sane.”

Good managers, in some cases and across different sectors, were directly responsible for people remaining at work, and working well. They were proactive and flexible. They were role models for behaviours for a future generation of leaders and inspire their teams to take part in open dialogue, mental resilience and better work.

COMMON CONCERNS FROM EMPLOYEES WITH THEIR ORGANISATION’S APPROACH TO MENTAL HEALTH

During interviews and surveys, employees offered a number of insights that highlighted where organisations didn’t get mental health support right. Many areas for improvement were highlighted and the most common themes raised by employees are noted below.

Employee concerns about senior leaders:

Employees wanted senior staff to engage with the mental health agenda. However, they felt a lack of open discussion about mental health by senior leaders cascaded negatively through an organisation. Stigma thrived when organisations adopt a ‘culture of secrecy’.

“I hear terms like ‘nutters’ flying around the office. I hesitate to ask for adjustments.” Financial Services Company

Workers who had mental health problems said there were rarely any positive messages about mental health management from the top – so middle management had no role models to copy when it came to their teams.

“There is a culture of being praised for coming in, even when you are sick.” Private company

Where there were wellbeing strategies and activities, these were jettisoned during busy times. Most challenging of all was where a target-driven culture became the norm – which had brutal effects on teams and individuals.

Employee concerns about Human Resources and Occupational Health:

“I pleaded for an Occupational Health referral but it never happened.” LA CC

Workers missed opportunities to receive assistance for mental health problems when the process for support wasn’t clear. The roles of Human Resources and Occupational Health professionals were often confused in the minds of employees. Interviewees cited a lack of specialist knowledge within Human Resources, poorly written ‘people’ policies ‘hidden away’ on the intranet and punitive absence procedures.

These situations were barriers to early intervention and stopped the help reaching those who needed it. Short-term absence can become long-term when opportunities for intervention are missed.

“On my first day back [after two weeks off with stress] I got loads of stuff thrown at me. I left within the hour. No one even asked me how things were.” Public Sector

In a few cases, absence procedures were badly communicated and used punitively by managers – with employees returning from absence to immediate disciplinary meetings. Workers often wished mental health received the same priority of attention as physical injury.

Employee concerns about managers:

People in teams reported when their manager’s confidence was stronger than their capability to provide mental health support. For example, some managers simply didn’t know how to handle a conversation about mental health, ignored signs when their team was struggling or dismissed pleas for help.

“Just saying, “Are you okay is not enough.” Team member

Some manager support was heavyhanded (e.g. the removal of all but basic tasks). Some lacked planning (e.g. returns from absence were not phased). And some employees reported instances of breaches of confidentiality.

“Shut up and get on with it.” Public Sector

The most common criticism was poor execution of basic managerial duties which led to feelings of isolation and a lack of control for individuals. Dropped one-to-ones, micro-management, out-ofhours phone calls and avoiding discussing wellbeing were harmful for workers.

CHALLENGES FACED BY EMPLOYEES INTERVIEWED FOR THIS REPORT

“I always end up dragging myself in. Some days I’m struggling and end up doing almost nothing at work.” Public Sector

Employees struggled when there was no personal resilience training, or no effort made to publicise the available support. They described a perceived lack of care for remote workers, support staff, volunteers and ancillary workers.

Individuals reported taking time off for mental health reasons and hiding the true reason for absence. Sometimes they would return to exactly the same working situation without flexibility or adjustments.

“I go until I break. People aren’t covered when they’re off sick.” LA

In cases, employees who had previously scored highly in appraisals underperformed. Some felt their career progression had been halted or they wanted to leave the organisation.

SUPPORTING EMPLOYEES WITH POOR MENTAL HEALTH

Recommendations: planning support for employees

In each Healthcheck, organisations were asked how well they supported their employees with mental health problems, and how openly mental health was talked about. These two central questions were important in helping to understand whether employees with mental health problems were well supported within their workplace.

Across the Healthchecks, organisations appeared to be at different stages in terms of creating a work environment where employee mental health is well supported and where mental health is openly talked about. In order to progress towards a supportive and open environment or culture in the workplace, the Healthchecks identified important stages that may enable this to happen.

The stages of development identified by the Healthchecks map closely onto Burke and Litwin’s (1992) model of organisational performance and change, a model used widely to assess how effective changes occur and what factors influence this. This model has been used to inform the recommendations below. These aim to guide anyone looking to develop an organisational culture which supports employees with experience of poor mental health effectively and encourages the whole workforce to speak openly about mental health.

The recommendations below are outlined in a suggested order of stages that will best support organisations and employers wanting to take this work forward. They are intended to be flexible and whilst there might be defined stages, it is likely that an organisation may have to repeat different recommendations, complete them simultaneously or pick and choose suitable and appropriate best practice at different times.

Preparation: Consider the External and Internal Environment

Understand legislation around mental health

Recognise the financial gains

Consider the size and type of your organisation and the resources available for change e.g. choosing strategies appropriate for budget and resources within your organisation.

Stage 1: Developing the foundations

Leading from the top – senior leaders prioritise mental health and champion positive behaviours and attitudes.

Example: A Chief Executive of a Political Party championed improved communication concerning mental health and personally took responsibility for implementation of Healthcheck recommendations.

Creating champions to lead the way – create an ‘action group’ to lead on change and champion improved ways of working; an action group made up of people with influence who want to champion change. Example: A UK Police Force established a Mental Wellbeing Network made up of staff from across the service interested in changing practices around mental health.

Developing wellbeing – build employee wellbeing into the values of the organisation and outline how this can be achieved across the organisation. Example: A Government department developed a three-year Staff Wellbeing Strategy, identifying supporting staff wellbeing as a key priority for the organisation.

Communicating a new way forward – develop a campaign to promote the importance of mental health through existing and creative communication processes. Example: A financial services organisation has used its staff handbook to excellent effect. The language and tone is warm and friendly yet firm. As the home of all HR policies and Code of Conduct, it is vital this document speaks the language of employees.

CASE STUDY of an organisation at Stage 1:

Context: A medium sized private organisation supplying health services undertook the Time to Change Healthcheck in 2014. The organisation had undergone a great deal of change and recognised the need to change practices around mental health. Employees reported their mental health as good, and there were positive aspirations from staff.

Points for Consideration: The organisation needed to start by developing a mental health strategy and ensure that line managers, senior leaders and HR became more aware of mental health issues. Line managers needed more support and changes made to current working practices, including a review of flexible working practices.

Healthcheck Recommendations:

- Develop a mental health strategy, ensure this is championed by senior leaders and line managers.

- Build this strategy into other policies and review current sickness policy and flexible working policies.

- Target training on mental health with motivated managers in order to develop mental health experts to implement a culture shift.

Stage 2: Building upon the foundations

Develop a meaningful policy – develop a clear mental health policy in collaboration with people with experience of mental health problems. Include case studies to bring the information to life and make the guidance easy to access. Example: The HR team within a charity developed a mental health policy which was reviewed by staff with personal experience. They updated the policy every two years and made it real through training. The policy ensures that mental health is considered when thinking about recruitment processes and development opportunities.

Supporting and developing managers – train existing and new managers on mental health, mental health policy and supporting staff with mental health problems. Ensure wellbeing and mental health is made part of the line management role and existing practices, and also create management forums for sharing good practice. Example: An NHS Trust ensured that all new managers have to go through training, including essential knowledge around mental health management.

Getting the right support structures in place – ensure that the organisational structure has support structures in place for managers, staff and volunteers and access to expertise. Example: A local arts organisation has a very flat management structure. Managers are critical to cascading information about mental health support in the right tone. Every single person who has disclosed their mental health problem has received help.

Creating space for wellbeing – develop wellbeing activities and a knowledge resource for all employees. This could potentially include activity classes, talks from mental health professionals, wellbeing days and internal wellbeing website. Example – A healthcare organisation developed a cross organisational ‘culture team’ which runs wellbeing activities throughout the year, such as singing groups.

CASE STUDY of an Organisation at Stage 2

Context: A financial services group employing thousands of people across the UK undertook the Time to Change Healthcheck in 2014. Employees hold the organisation in high regard and leaders and managers were on board with supporting and developing a culture of positive mental health.

Points for Consideration: Wellbeing policies existed but employees needed to be made more aware of the resources on offer. Consistency of support was also needed with further training and an improvement in general line management skills. Leaders working outside of main locations needed to be able to access advice on how to manage mental health at work and a greater culture of wellbeing needed to be created.

Healthcheck Recommendations:

- Develop new ways of communicating wellbeing resources, e.g. a short film, and ensure policy is the responsibility of all leaders within the organisation.

- Maximise existing resources such as Occupational Health, employee relations and leaders working with staff with mental health problems to develop mandatory mental health training. Also set up a steering group to develop best practice examples.

- Ensure managers working in remote locations have access to support lines and consider connecting with more experienced managers.

- Promote staff wellbeing groups, develop a connection of wellbeing champions, create a selection of personal stories for sharing and encourage senior leaders to ensure more of a work-life balance.

Stage 3: Reviewing progress on new ways of working

Review how it’s going – review existing working practices and employee perceptions of practices. Act on employee recommendations and focus on contribution of the workload, including lone working and skills training on mental health. Example – A financial firm recognised the impact of increased workload on mental health and conducted a capacity review across the organisation.

Being flexible – develop flexibility in your approach around managing mental health problems – recognising that people may need different adjustments within work. Example – A charity offered extra supervision for staff managing increased complexity in working with service users.

Increasing the energy – ensure motivation for change continues and keep mental health on the agenda through mental health networks, champions, and awareness raising activities. Example – A Housing Trust regarded physical health as closely linked to mental health and established a Wellness Centre providing annual physical health check ups to continue supporting awareness around wellbeing.

CASE STUDY of an organisation at Stage 3

Context: A medium sized charity working on a range of high-profile campaigns completed the Time to Change Healthcheck in 2013. Employees felt the organisation manages mental health well and that managers work hard to support colleagues with mental health issues.

Points for Consideration: Mental health policy and support mechanisms were in place, managers had received mental health training and staff were very positive about working for the organisation. Staff were stressed due to working long hours and a deep commitment meant work-life balance needed to be addressed.

Some staff may need different types of training in order to meet the demands of their role and the momentum around talking about mental health and attending to it needed to be increased.

Healthcheck Recommendations:

- Review levels of stress at work and consider how to ensure employees balance work with other aspects of their lives.

- Ensure flexible training arrangements for staff and if specialised training is required, ensure this is regularly updated.

- Keep momentum going by developing more regular check-ins with staff on mental health and ensure current support systems and policies are cascaded by the leadership team to ensure best practice is being modelled.

Stage 4: Keeping the Momentum Going

Getting some feedback – develop mechanisms for feedback and use existing wellbeing data through staff surveys, turnover and absence data and sharing of good and poor practice. Example – a Government department used their staff survey and feedback from training events to launch a series of initiatives centred on developing a culture that supports wellbeing.

Making more changes – use feedback and evidence from best practice to refine and modify processes. Example: one local authority has recently introduced a new absence policy designed to manage the staff illness process better. However, managers are not using it correctly and employees feel it is punitive. A peer review will help communicate it better and be more effective.

Becoming the norm – ensure that talking about and supporting mental health becomes a normal way of working, through reviewing whether mental health conversations and management are part of everyday working practices. Example – a PR agency ensured that specific questions related to mental health were included on annual 360 degree appraisal processes so consistent review and management can occur every year for staff around their wellbeing.

CASE STUDY of an Organisation at Stage 4

Context: A small media communications company completed the Time to Change Healthcheck in 2015. Employee Wellbeing was considered as a central value to the organisation and part of their mission statement.

Points for Consideration: Mental health policy, support mechanisms and wellbeing activities were all in place within the organisation. However, although appraisal processes were in place, employees felt that more regular meetings with managers was important to understand further issues around mental health. Employees reported feeling stressed due to issues around personal control concerning workloads and they also wanted to further improve and promote wellbeing so it didn’t become something that was just done once.

Healthcheck Recommendations

- Act on feedback and increase both line management training opportunities and 1-1 meetings.

- Review employee stress by understanding more about workload control and current workload; act upon reviews and develop appropriate interventions e.g. organisational or individual stress plans; and explain what is being done about it.

- Reignite wellbeing initiatives: wellbeing check ins at the beginning of meetings, ensure lunch breaks are taken and activities offered, hold discussions and forums about mental health practice.

CLOSING REMARKS

It is often said by organisations that ‘our people are our most important asset’. This has never been more true. If we primarily employ people for their minds, it makes business sense to ensure employees are as mentally healthy and as productive as possible. Many of the UK’s leading employers have woken up to the importance of mental health and wellbeing in the workplace. In this report we have heard from employees about the current state of mental health support in their workplace.

We need to celebrate the many excellent examples of good practice and share these positive stories so that others can benefit from them. Equally, we need to acknowledge that there is work to be done to achieve fair and consistent treatment of people with mental health problems in the workplace.

The common attributes of good organisations are to listen to what their employees are saying about their mental health and wellbeing, commit to positive changes to address these issues and find robust ways of measuring their performance on these commitments. We hope this report will help organisations who are prepared to start this journey.

Source: Time-To-Change